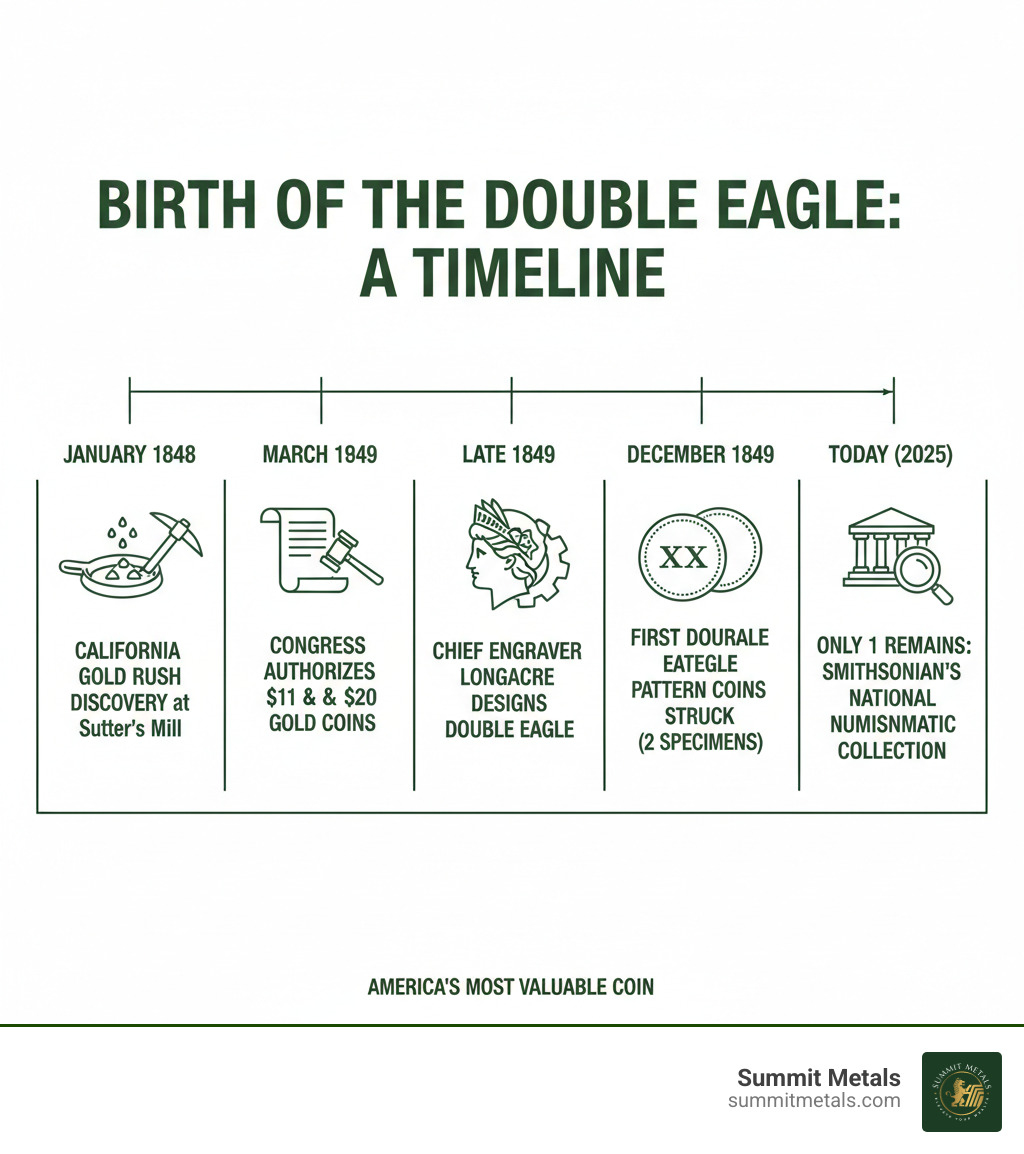

Why This Coin is America's Most Valuable Numismatic Treasure

The 1849 coronet head gold $20 double eagle unique smithsonian collection represents the rarest and most valuable coin in American history. This singular specimen holds immense significance as:

- Only surviving example - Just one specimen exists worldwide

- Pattern coin status - Created to test the new $20 denomination design

- California Gold Rush connection - Direct result of the 1849 gold findy

- Smithsonian home - Housed in the National Numismatic Collection

- Estimated value - Worth $10-20 million if ever sold at auction

- Historical importance - First attempt at America's largest gold coin denomination

The California gold rush of 1848 changed everything for American coinage. When gold started pouring out of California, it lowered gold's value against silver so much that people were melting silver coins for export. Congress needed a solution fast.

In March 1849, they authorized two new gold denominations: a tiny $1 gold piece and a massive $20 "double eagle." The double eagle was designed to handle large transactions more efficiently than the existing $10 eagle coins.

Chief Engraver James B. Longacre faced fierce opposition from Philadelphia Mint officials when creating this groundbreaking design. Despite the political battles, two pattern coins were struck in late December 1849. One disappeared long ago, leaving only the Smithsonian's specimen as proof of this numismatic milestone.

I'm Eric Roach, and during my decade as an investment banking advisor in New York, I've guided clients through complex hedging strategies and helped them understand how precious metals like the 1849 coronet head gold $20 double eagle unique smithsonian collection represent the pinnacle of tangible asset value. Today, I help everyday investors apply these same institutional-level strategies to build wealth through physical gold and silver.

The Birth of a Legend: Historical Context of the Double Eagle

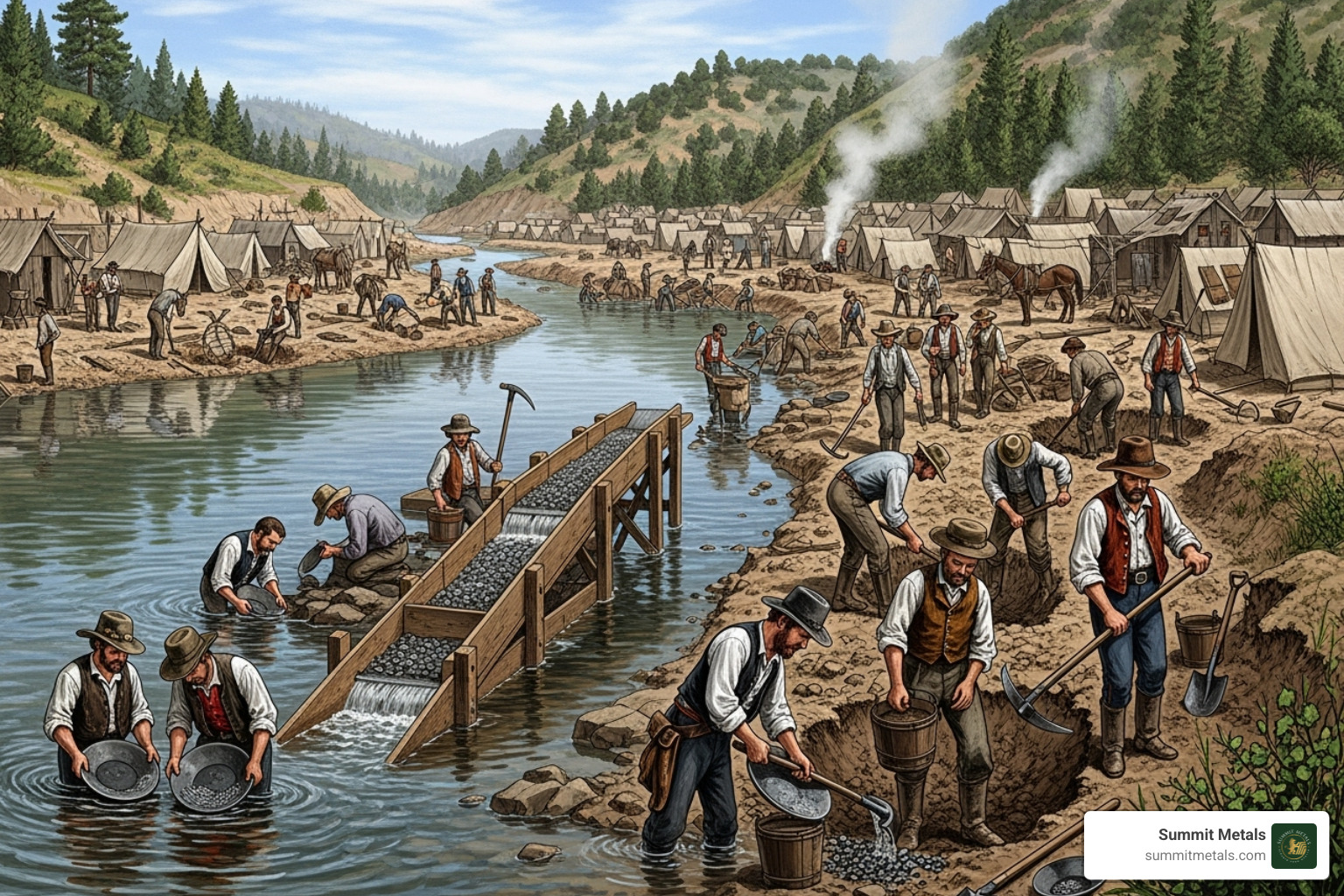

Picture this: it's 1847, and the biggest gold coin in America is worth just $10. That's the "Eagle," and for most folks, it's plenty of money. But then something extraordinary happened that would change American coinage forever.

On January 24, 1848, a carpenter named James W. Marshall spotted something glinting in the water at Sutter's Mill in California. That tiny findy sparked the California Gold Rush and set in motion events that would create the 1849 coronet head gold $20 double eagle unique smithsonian collection.

Within months, hundreds of thousands of "Forty-Niners" were racing west with dreams of striking it rich. And many of them did. Gold started flowing into the Philadelphia Mint in amounts no one had ever seen before. Suddenly, the modest $10 Eagle seemed woefully inadequate for handling all this precious metal.

The massive influx of gold bullion created an unexpected problem. When you flood the market with gold, its value drops compared to silver. This might sound like an economics textbook, but it had real-world consequences that affected every American's pocket.

For a deeper understanding of how gold has shaped monetary systems throughout history, check out A Brief History of Gold as Currency and Store of Value.

The Economic Shift That Demanded a New Coin

Here's where things got interesting. The gold versus silver value shift created a golden opportunity—literally—for smart bullion dealers. They figured out they could buy silver coins at face value, melt them down, and sell the silver for more than what they paid. It was perfectly legal arbitrage.

But this clever scheme had a downside. Silver coins started disappearing from circulation faster than ice cream on a hot summer day. People couldn't find silver dollars or half dollars to make change. The nation's silver coinage was literally being melted away and exported overseas.

Congress needed to act fast. Easing pressure on silver became a national priority. A forward-thinking North Carolina Congressman proposed creating gold dollars that could circulate alongside the disappearing silver ones. It was a smart idea, but someone had an even better one.

In what can only be described as brilliant political maneuvering, a last-minute bill amendment added authorization for a much larger coin—the $20 Double Eagle. Sometimes the best ideas come at the eleventh hour.

From Legislation to Creation

The Coinage Act of 1849 officially gave birth to two new coins: the tiny gold dollar and the mighty Double Eagle. While the gold dollar quickly rolled off the presses, the Double Eagle proved more challenging to create.

The authorization of $1 and $20 gold coins was genius in its simplicity. The gold dollar helped with everyday transactions, while the Double Eagle was designed for the big leagues. Think of it as the difference between a pickup truck and an 18-wheeler—both useful, but for very different jobs.

The Double Eagle's practicality for large transactions made it an instant hit with banks and merchants. Instead of counting out twenty gold dollars or carrying two $10 Eagles, you could simply use one magnificent $20 piece. It was the ultimate "banker's coin"—designed for people who moved serious money.

This wasn't just about convenience. The California Gold Rush had transformed America into an economic powerhouse, and the country needed currency that matched its new status. The 1849 coronet head gold $20 double eagle unique smithsonian collection represents this pivotal moment when America's money grew up along with its economy.

For modern investors interested in how gold continues to serve as a store of value, explore Changing Fiat Currency into Real Money: Paper Dollars to Gold.

Design and Controversy: The Making of the 1849 Coronet Head Gold $20 Double Eagle

When Congress authorized the new $20 gold coin, the monumental task of designing it fell to James B. Longacre, the Chief Engraver of the U.S. Mint since 1844. What should have been an exciting artistic challenge quickly turned into a political nightmare that would test Longacre's resolve and skill.

Longacre was a talented artist, but he walked into a hornet's nest of internal Mint politics. His biggest adversary was Franklin Peale, the Mint's Chief Coiner and son of famous painter Charles Willson Peale. Peale wielded considerable influence within the Philadelphia Mint and seemed determined to make Longacre's life difficult at every turn.

The technical challenges were enormous even without the office politics. The new double eagle's 34mm diameter made it one of the largest coins ever attempted by the U.S. Mint. Longacre's ambitious high-relief design pushed the limits of the Mint's machinery, leading to repeated problems with die splitting during the striking process.

Some accounts suggest Peale's opposition went beyond mere professional disagreement. There were whispers of deliberate sabotage, with Longacre's models mysteriously damaged and equipment "malfunctioning" at crucial moments. Despite these obstacles, Longacre pressed forward, determined to create something worthy of America's new economic power. His perseverance through these trials is well documented in historical works like Numismatic Art in America.

Key Design Elements and Specifications

Longacre's final design for the 1849 coronet head gold $20 double eagle unique smithsonian collection became an instant classic. The obverse design features Liberty in profile, facing left with her hair neatly tied back. She wears a coronet inscribed with "LIBERTY", giving the coin its "Coronet Head" nickname. Thirteen stars representing the original colonies surround her head, with the date "1849" positioned at the bottom.

The reverse design showcases a powerful heraldic eagle with shield, clutching an olive branch for peace and arrows for defense. Rays of glory shine above the eagle's head, while the inscriptions "UNITED STATES OF AMERICA" and "TWENTY D." circle the rim. This early pattern is a "No Motto" variety, meaning it lacks the "IN GOD WE TRUST" that would appear on later coins during the Civil War.

The coin's physical specifications were impressive for their time. At 34mm diameter, it commanded attention and respect. The 33.4 grams weight gave it substantial heft, while the 90% gold, 10% copper composition provided durability without sacrificing precious metal content. This was serious money in physical form.

The Rumor of a Second Specimen

Here's where the story gets intriguing. Historical records show that two patterns struck in late December 1849, but only one survives today. One specimen for the Mint Cabinet eventually found its way to the Smithsonian, where it remains the crown jewel of American numismatics.

The mystery surrounds the second specimen for Treasury Secretary William M. Meredith. This coin was reportedly presented to Secretary Meredith as a courtesy, but then it simply vanished from history. The disappearance of the second coin has fueled decades of speculation and treasure hunting among collectors.

While most experts consider its unconfirmed existence highly unlikely after more than 170 years, the possibility keeps hope alive in numismatic circles. Adding to the intrigue, a gilt brass specimen appeared in an 1892 auction, likely a trial strike rather than a genuine gold coin, but proof of the experimental nature surrounding this legendary piece.

The 1849 coronet head gold $20 double eagle unique smithsonian collection remains truly unique, making it not just rare but irreplaceable. Its singular survival transforms it from a simple coin into a priceless artifact of American history.

A Priceless Artifact: The Unique Smithsonian Collection Specimen

The 1849 coronet head gold $20 double eagle unique smithsonian collection stands as more than just a remarkable coin—it's truly a national treasure that captures a pivotal moment in American history. When you walk through the halls of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., you're witnessing something extraordinary: the only surviving example of America's first attempt at a $20 gold coin.

This incredible specimen is housed within the prestigious National Numismatic Collection, where it holds the technical classification of Judd-117 and Pollock-132. These numbers might seem dry, but they tell an important story—they mark this coin as a pattern piece, an experimental design that was never intended for regular circulation. Instead, it served as a test run for what would become one of America's most important coin denominations.

What makes this coin so special isn't just its age or beauty, but its absolutely unique status. There's literally no other coin like it anywhere in the world. You can explore its official documentation and learn more about its place in the collection at the Smithsonian's official record.

Why is the 1849 Coronet Head Gold $20 Double Eagle a unique Smithsonian collection piece?

The story of why this coin is so incredibly rare begins with simple math—there's only one known specimen in existence. In coin collecting, this earns it the highest possible rarity rating of R-10.0 on the Sheldon scale, a designation reserved for coins with only one to three known examples. For our 1849 Double Eagle, it's definitively just one.

But rarity alone doesn't tell the whole story. This coin carries an unbroken historical provenance that traces directly from the Philadelphia Mint in December 1849 straight into the official Mint Cabinet, which eventually became part of the Smithsonian's collection. This clear chain of custody eliminates any questions about authenticity—we know exactly where this coin has been for the past 175 years.

The historical significance runs even deeper when you consider this coin's direct connection to the California Gold Rush. Every gram of gold in this coin represents the economic earthquake that shook America when gold started pouring out of California. It's not just a coin—it's a physical piece of one of the most important economic events in our nation's history.

As the first attempt at a $20 denomination, this pattern coin represents the birth of what would become a cornerstone of American commerce. The fact that it was struck as a proof specimen—meaning it was specially made with polished dies and extra care to showcase the design—shows that even the Mint officials knew they were creating something special.

The Unrivaled Value and Legacy

When experts try to put a dollar figure on the 1849 coronet head gold $20 double eagle unique smithsonian collection, they run into a fascinating problem: how do you price something that's literally priceless? Since this coin belongs to the American people and will never be sold, any valuation is purely theoretical. But that hasn't stopped experts from trying.

Current estimates place its value somewhere between $10 million and $20 million if it ever came to auction. The USA Coin Book gets even more specific, estimating its proof condition value at an eye-watering $19.2 million. To put that in perspective, the gold content alone is worth about $3,039 at today's prices—meaning the historical and numismatic value adds nearly $19 million to a few thousand dollars worth of gold.

The coin's legendary status isn't new. Back in 1909, the famous financier J.P. Morgan offered $35,000 for this coin—an absolutely massive sum that would equal well over $1 million in today's money. Even a century ago, smart money recognized this coin's unique place in history.

What's remarkable is how the coin's reputation has only grown over time. When numismatic experts are asked which single coin they'd most want to own from all of American coinage, the 1849 coronet head gold $20 double eagle unique smithsonian collection consistently tops the list. Its combination of rarity, beauty, and historical significance creates a perfect storm of desirability that no other U.S. coin can match.

The evolution from J.P. Morgan's $35,000 offer to today's multi-million dollar estimates shows how our understanding and appreciation of this coin's importance has deepened over the decades. It's not just valuable—it's become the crown jewel of American numismatics, a status that seems only to grow stronger with each passing year.

Comparing the 1849 Double Eagle to Other Numismatic Legends

When we talk about the 1849 coronet head gold $20 double eagle unique smithsonian collection, we're discussing a coin that sits at the very pinnacle of American numismatics. But it's not alone up there. The United States has produced several other legendary coins that command astronomical values and capture collectors' imaginations worldwide.

What makes these coins so special isn't just their rarity—it's the incredible stories behind them. Each represents a pivotal moment in American history, when economics, politics, and craftsmanship collided to create something truly extraordinary.

The world of ultra-rare coins is fascinating because each specimen tells a different story about America's relationship with precious metals. Understanding how gold has maintained its value throughout history helps explain why these coins continue to appreciate, as explored in Why Gold's Return Is Higher Than You Think.

| Coin | Rarity | Estimated Value (USD) | Historical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1849 Coronet Head $20 Double Eagle | Unique (1 known) | $10-20 Million | First $20 gold pattern, direct result of California Gold Rush, birth of a new denomination |

| 1933 Saint-Gaudens $20 Double Eagle | Extremely Rare (Few) | $10-20 Million | Symbol of end of U.S. circulating gold coinage, subject of legal battles, most valuable coin legally owned by private citizens |

| 1804 Draped Bust Silver Dollar | Extremely Rare (15) | $4-7 Million | "King of American Coins," diplomatic presentation piece, iconic early U.S. dollar |

The 1933 Saint-Gaudens Double Eagle

The 1933 Saint-Gaudens Double Eagle represents the end of an era in American coinage. Unlike our 1849 pattern coin, millions of 1933 Double Eagles were actually minted at the Philadelphia facility. But here's where the story takes a dramatic turn.

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 6102 in 1933, he effectively ended the circulation of gold coins in America. Citizens were required to turn in their gold coins to be melted down as the country moved away from the gold standard. Most of those freshly minted 1933 Double Eagles never saw the light of day—they went straight to the melting pot.

The few specimens that survived did so illegally. Someone—we still don't know who—managed to smuggle a handful of these coins out of the Mint before they could be destroyed. For decades, ownership of these coins remained illegal, creating a cat-and-mouse game between collectors and the government.

Only one specimen, known as the Farhi-King coin, was ever legally monetized by the government. This single coin sold for $7.5 million in 2002, then shattered records again in 2021 when it brought $18.9 million at auction. The 1933 Double Eagle's story is one of government intervention, clandestine collecting, and the end of America's circulating gold coinage.

The 1804 Draped Bust Silver Dollar

The 1804 Draped Bust Silver Dollar earned its nickname "The King of American Coins" through sheer audacity and historical intrigue. Despite bearing the date 1804, not a single one of these coins was actually struck in that year. Talk about numismatic mystery!

These coins were created decades later as diplomatic presentation pieces, designed to showcase American craftsmanship to foreign dignitaries and heads of state. The U.S. Mint wanted to demonstrate that America could produce coins as beautiful and sophisticated as any European nation.

Only fifteen specimens are known to exist today, divided into three distinct classes based on when they were struck and their specific characteristics. Class I specimens were struck in the 1830s for diplomatic gift sets, Class II coins appeared in the 1870s, and Class III represents a single specimen struck for a collector in 1876.

These coins embody America's early diplomatic efforts and the young nation's desire to establish credibility on the world stage. Each specimen represents not just numismatic artistry, but America's growing confidence as a world power.

The comparison between these three legendary coins shows how different historical forces can create numismatic treasures. The 1849 coronet head gold $20 double eagle unique smithsonian collection represents innovation and westward expansion. The 1933 Double Eagle symbolizes government intervention and the end of the gold standard. The 1804 Silver Dollar reflects diplomatic ambition and early American craftsmanship.

What unites all three is their connection to precious metals and the enduring value that gold and silver represent. While most of us will never own coins worth millions, we can still participate in the precious metals market through more accessible options, building wealth the same way institutional investors do.

From Priceless Relics to Modern Investments

While the 1849 coronet head gold $20 double eagle unique smithsonian collection sits safely behind glass at the Smithsonian, the same spirit that drove collectors to treasure this legendary coin lives on today. You might not be able to own that priceless artifact, but you can absolutely build your own meaningful collection of precious metals.

The beauty of numismatic collecting extends far beyond museum pieces. Today's gold market offers incredible opportunities for both seasoned collectors and newcomers looking to diversify their portfolios. Modern gold coins like American Eagles and American Buffalos carry the same fundamental appeal that made the 1849 Double Eagle so captivating - they're tangible wealth you can hold in your hands.

At Summit Metals, we see this connection every day. Our clients understand that investing in physical gold isn't just about portfolio diversification - it's about owning something real in an increasingly digital world. These tangible assets don't disappear with a market crash or get wiped out by a computer glitch.

When you're starting your gold investment journey, one of the first decisions you'll face is choosing between coins and bars. While both offer excellent value, gold coins provide a unique advantage that connects directly back to our 1849 Double Eagle story - government backing and legal tender status.

Gold coins carry a face value protected by fraud laws, meaning they have additional legal protections that pure bullion bars don't offer. This face value also makes them more liquid in many markets, easier to sell in smaller quantities, and often more appealing to collectors. For a deeper dive into this decision, check out our guide on Gold Bars vs. Coins.

Building Your Own Gold Collection

The most successful gold investors don't try to time the market or make one massive purchase. Instead, they use a strategy called dollar-cost averaging - the same approach many people use with their 401(k) retirement accounts.

This is where Summit Metals' Autoinvest strategy becomes incredibly powerful. Rather than worrying about whether gold is at its perfect low point, you can make consistent monthly purchases that build your position over time. Some months you'll buy when prices are higher, others when they're lower, but over the long term, you'll average out to a solid entry point.

Think of it as fractional gold ownership that grows steadily. You might start with a single 1/10-ounce American Gold Eagle one month, add a 1/4-ounce coin the next, and gradually build toward full ounces or even larger bars. This approach takes the stress out of timing and makes gold investment accessible regardless of your budget.

The strategy mirrors how the 1849 coronet head gold $20 double eagle unique smithsonian collection came to be - it wasn't created overnight, but rather as a response to changing economic conditions and the steady accumulation of California gold. Your collection can grow the same way, responding to your financial goals and market conditions.

For those interested in the mathematical approach to this strategy, our detailed guide on The Strategic Approaches to Investing in Gold and Silver: Dollar Cost Averaging and Value Averaging breaks down exactly how to implement these techniques effectively.

The key is starting. While you may never own a coin worth $20 million like the Smithsonian's treasure, you can absolutely build a meaningful precious metals portfolio that serves as your own hedge against economic uncertainty.